WORRIED ABOUT MEASLES?

Are you worried about measles here in the United States? Before 1963, when a single dose measles vaccine was introduced, measles was not considered a serious disease. Parents even welcomed the disease in their children, as it promised lifetime immunity. In 1960, the mortality rate of measles was 1 in 500,000!

The single dose measles vaccine was responsible for a dramatic drop in measles. Years later, a two-dose vaccine (MMR-measles, mumps, and rubella) and a population wide rollout of the measles vaccine led to the complete elimination of measles in 2000 in the United States. Since the efficacy of the vaccine is over 90 percent, it is essentially impossible for the virus to spread or return in a population where nearly 95 per cent of the people have been vaccinated.

So why are we hearing about outbreaks of measles here in the U.S.? The answer is that unfortunately, measles has not been eradicated globally, and the rest of the world is not doing well with the disease. Outbreaks can be found actively circulating in other countries.

Cases of measles are up around the globe 79 per cent from 2022. Europe has seen a 30-fold increase. In 2022, there were 941 measles cases in Europe. In 2023, there were over 30,000 cases. The world Health Organization reported an 18% increase in cases globally from 2021 to 2022 to 9 million, and a 43% jump in deaths, to 136,000.

When we see measles cases in the U.S., the infections usually happen when travelers abroad bring the virus back with them. Outbreaks can happen when an imported case of measles spreads to areas of unvaccinated individuals.

HOW DOES MEASLES CAUSE HARM?

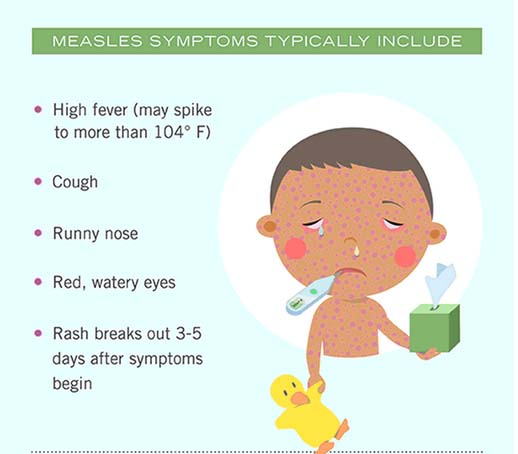

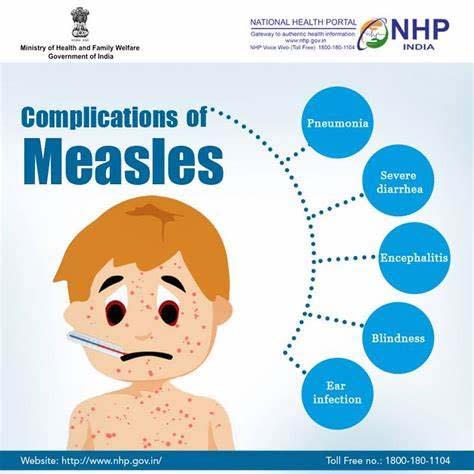

The measles virus enters through the respiratory tract and then spreads through the bloodstream to other parts of the body. The disease usually starts with a fever, cough, dripping nose, and conjunctivitis and continues with a rash which spreads from the head to the feet. It can lead to an intense inflammatory reaction that can result in severe disease, pneumonia, and death. Although most people will recover without any long-term issues, those who are pregnant and those who are under 20, especially younger children, are vulnerable. According to the CDC, around 20% of those who get the disease will be hospitalized.

SO WHY ARE WE STILL AT RISK FOR MEASLES OUTBREAKS?

We are still at risk for measles outbreaks here because our vaccine coverage has been slipping. In 2021, 92 per cent of children under two years of age got at least one dose of the measles vaccine but only 79 percent of older children got the required two doses. When vaccination rates go down, measles cases go up.

There are several reasons for the slippage in coverages:

- One reason is that in some areas such as Florida, which currently is seeing an upswing in cases, parents are being told that it is up to them whether they should send their unvaccinated children to school during an outbreak.

- Another reason is the disruption to vaccination campaigns that was pandemic-related, as well as anti-vaccine sentiment due to misinformation.

- Also, it is difficult to convince people of today of the dangers of measles, from pneumonia to brain inflammation, when many young people have never seen a case in their entire lives.

CAN MEASLES

BECOME ENDEMIC AGAIN?

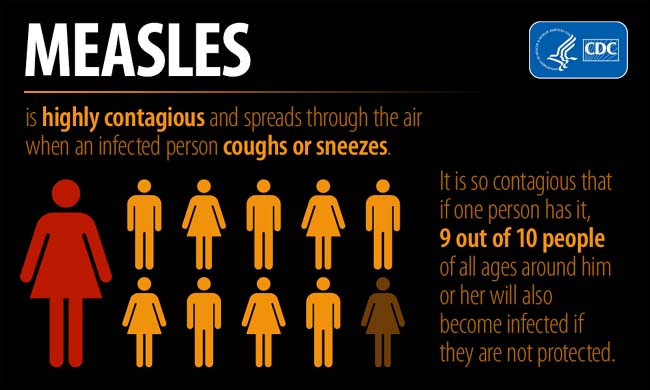

We know the measles virus is highly transmissible and an airborne virus. The infection rate is much higher than for the COVID virus. Even though measles was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000 and most children here are required to be immunized to attend school, should we be worried that measles could become endemic (frequently occurring) again?

Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, as well as religious and medical exemptions to vaccines in the U.S. and other countries leave populations where children and even adults are susceptible to the virus. This leaves a potentially substantial risk of importation and spread of measles in the U.S.

It is recommended by the CDC that anyone over the age of 6 months who is traveling internationally get vaccinated. A dose at this age can provide protection during travel. Parents of infants between 6 and 12 months should think about getting their infants vaccinated regardless of whether they are traveling overseas. Although it may not lead to long-term protection, it could still be lifesaving.

THE BEST WAYS TO PREVENT MEASLES

Here are the best ways to prevent measles:

- If you are old enough to have had measles as a child, you are probably immune.

- If you have had two doses of the measles vaccine, you are very unlikely to catch measles.

- If you are not sure, a routine blood test that measures antibody levels will be the confirmation you need.

The general population of the United States usually did not have to worry about outbreaks of measles. That was usually only reserved for health-care workers and other high-risk groups. However, given the current global situation, it would be prudent to check your risk for measles should you travel abroad.

HISTORY OF MEASLES IN THE U.S.

1960s

Since in the United States before the 1960s, measles was not considered a serious disease, the development of a vaccine for measles dictated that public opinion about measles and the vaccine had to be changed.

Measles became the first disease to become the target of a federally supported eradication-through-vaccination campaign.

This could only happen because several facts were in place:

- The support of immunization of the federal government at the local level grew.

- The required vaccination of children was seen as the best means of ensuring a protected population.

- The belief that mass vaccination could not only help to manage infectious diseases, but it could also eradicate them.

- The focus of local and federally supported immunization initiatives began to extend to the diseases of childhood considered to be mild and moderate because they were less severe than previous mass vaccination campaigns such as smallpox, polio, and diphtheria.

In 1962 President John F. Kennedy, Jr signed the Vaccination Assistance Act, the first law directing federal funds to states for broad immunization efforts, with an emphasis on children.

In 1965, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, Congress renewed the program and extended it to cover measles.

In 1967, Johnson endorsed CDC’s plan to eliminate measles from the United States within a year. (Unfortunately, it took quite a bit longer to accomplish this.) The year 1967 saw the number of weekly cases of measles fall dramatically from an average of 1000 cases per week in the pre-vaccine era to 200.

In 1968 there were 22,000 cases, compared with an average of 450,000 cases per year in the pre-vaccine era.

1970s

In 1971, it was evident that something was very wrong with the mass vaccination program because the measles cases went up again to 75,000.

It was found that the vaccination program was not protecting all communities. For example, in Los Angeles, California, immediately after the introduction of the measles vaccine, the vaccines had been administered primarily by physicians in private practice, most of whom had patients who came from neighborhoods with predominately young middle-and upper-class white families. As a result, measles had quickly become a disease of the black population and those with Spanish surnames. And this was not unique to Los Angeles but across the U.S. as well. Also, of course, since more attention was being paid to measles, more cases were being reported.

It eventually became evident that requiring a vaccine by law addressed the problem of those whom health officials considered hard to reach either because of class, race, education, or language. (By 1979, all states had added measles to their compulsory immunization laws.)

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s administration launched the National Childhood Immunization Initiative, which funneled federal resources to states to encourage mass immunization and asked governors to ensure their immunization laws covered all recommended vaccines—a list that by then comprised polio, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, mumps, rubella, and measles. The Carter initiative brought immunization rates among children close to 90% across the board, an unprecedented level.

1980s

In 1981, which was Carter’s last year in office, 96% of all schoolchildren were vaccinated against measles and the number of measles cases was at an all-time low. By this time immunization protocols had been simplified due to the new technology of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine.

In the 1980s, vaccine hesitancy rose to the forefront with parents questioning the safety and necessity of vaccines for their children. It was historically a time of social reforms including patients’ rights, women’s rights, and environmental protection.

In 1986 the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act was passed, which required the federal government to inform parents of both the benefits and risks of vaccines and required vaccine providers to report vaccine injuries to federal authorities.

It also established the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Local organizations across the country began targeting laws requiring vaccines for school, calling for repeals and personal-belief exemptions to be added to the medical and religious exemptions.

1990s

At the beginning of the 1990s, the U.S. had an organized, national movement that was critical of vaccine safety, another movement working to erode mandates, and a dramatic resurgence of measles. The devastating measles outbreaks of 1989-1991 caused more than 50,000 cases and 150 deaths.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton’s first year in office, he placed access to childhood vaccines at the forefront of his administration’s health reform efforts (moved in part by the measles epidemics of the preceding years, which as in the 70s was largely caused by the lack of access to vaccines by disadvantaged populations.)

Clinton signed into law the Comprehensive Child Immunization Act which created an entitlement program called Vaccines for Children. VFC was to provide free vaccines for all Native American and Alaska Native children, children without insurance, children covered by Medicaid, and children whose insurance did not cover vaccines.

Although the Clinton administration had initially proposed free vaccines for all U.S. children, the program approved by Congress was a compromise. Nevertheless, it helped bring toddler immunization rates to historic heights by the end of Clinton’s first term and soon eliminated racial disparities in MMR vaccination rates.

Clinton’s last year in office would go down in public health history as the year measles was officially “eliminated” from the United States: the disease was no longer endemic, and the only remaining cases were imported from abroad or spread by such cases.

2000s

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) launched a program to investigate 8 vaccine safety concerns, including an MMR–autism link. In 2004, the IOM investigations concluded and found no connection between autism and any vaccines.

In 2011, the Lancet article published in 1998 by Andrew Wakefield linking autism to vaccines was retracted after it was found to be incorrect.

In 2014, the U.S. saw a large number of measles cases many associated with an outbreak among the Amish in Ohio.

In 2015, there was a multistate outbreak of measles tied to Disneyland which caused 129 cases of measles. Shortly after, California tightened school immunization laws.

In 2017, there was an outbreak of 65 measles cases in Minnesota linked to a Somali-American community with autism fears.

As of April of this year (2024), there have been 113 cases of measles reported.

Top of Are You Worried About Measles?

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566