VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

POLIO VS COVID

Vaccine Hesitancy

During the vaccine development for polio, vaccine hesitancy was essentially non-existent and the new Salk vaccine was widely and wildly accepted. In 1955, millions of American children were lined up by their parents to get inoculated against polio.

With the development of the vaccines for COVID-19, millions of American adults have been inoculated. And yet, there exists an unyielding number of Americans who are stubbornly vaccine hesitant.

Both the polio vaccines and the COVID-19 vaccines were and are a victory of science. So why the difference in acceptance? Let's take a look...

Similarities Between the Two Diseases

Many similarities can be noted between the polio epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. Both produced huge outbreaks throughout the country.

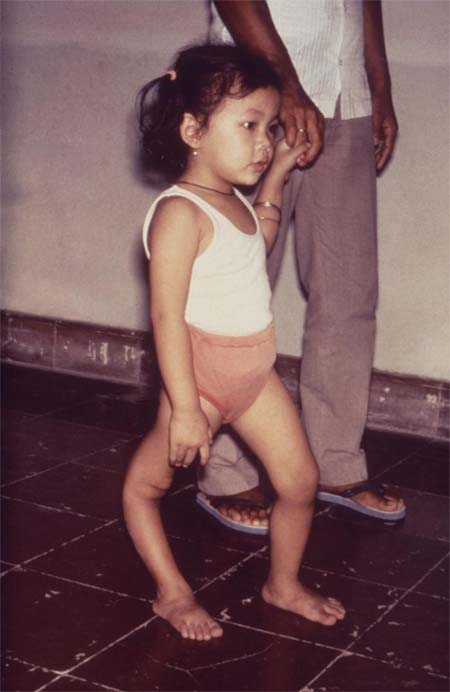

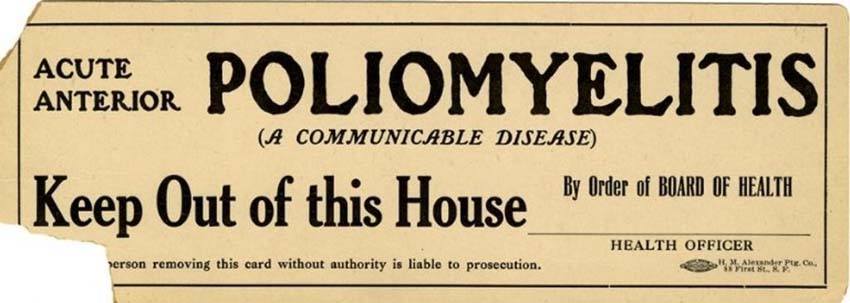

Polio disabled 35,000 people a year during the late 1940s and early 1950s, most of them children. Parents were terrified and voluntarily isolated themselves and their families. They tended to keep their children close to home, not allowing them to go to community gathering spots such as movie theaters, roller rinks or beaches.

As early on with COVID-19, it was not known how the virus was transmitted and, as with COVID-19, business and travel were affected.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the

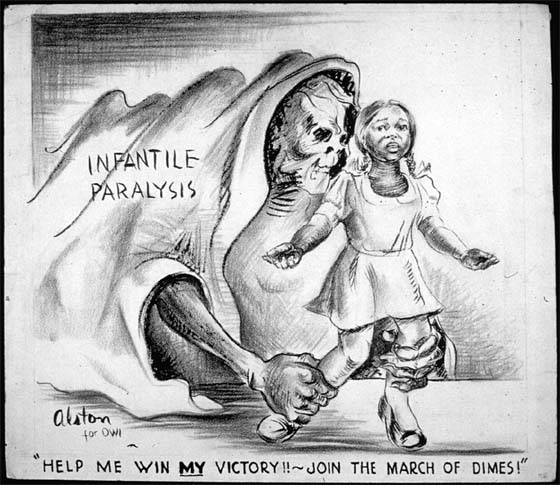

March of Dimes

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had lost the use of his legs at the age of 39 from a polio infection. He launched the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in the late 1930s, which was later renamed the March of Dimes. This foundation took the lead in efforts to fund research since the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was still in its infancy.

It was largely Roosevelt’s passion for finding some kind of solution, such as a cure or a vaccine, that made polio a priority in this country. His effort was akin to a call to action just as the war effort had been. And, in 1955 Americans had a deep respect for science.

Thousands of volunteers for the March of Dimes, primarily mothers, went door to door, distributing the latest information about polio. They asked for donations, even as little as a dime. As a result, dimes and dollars started pouring in and many donations were sent directly to the White House.

Americans at the time of the polio vaccine development felt they were invested in a solution, and the public at the time had confidence in the research leading up to the polio vaccine. In fact, when the Salk vaccine was ready for experimental testing in 1954, 600,000 children were volunteered by their parents as research subjects.

In 1952, at the peak of the epidemic, polio had infected nearly 60,000 children and more than 3000 died. By comparison, approximately a year’s worth of comparable statistics for the COVID-19 pandemic showed that more than 32 million people were reported infected and there had been more than 573,00 deaths. Between 1955 and 1962, more than 400 million doses of the polio vaccine were distributed, reducing the cases of polio by 90%.

Operation Warp-Speed and the COVID-19 Vaccine Development

As can be seen, there is a huge disparity between the way information was shared for polio and how COVID-19 information is shared today (as of October 2021), as well as how much of it is available. Perhaps Operation Warp Speed was not an ideal name for the project to spearhead vaccine development because it actually sounded like speed was prioritized over everything else.

However, even though the vaccines were rolled out quickly, the FDA and CDC thoroughly tested them and ensured their safety and efficacy. Still, there is a lingering hesitancy among some Americans to receive the increasingly available COVID-19 shots.

Back during the polio epidemic, the public generally trusted the medical community and believed in each other. This is not so today. American’s trust of the medical and scientific community is at an all-time low. Additionally, there is a continuing flood of disinformation on the internet about all vaccines.

Victory Over Polio!

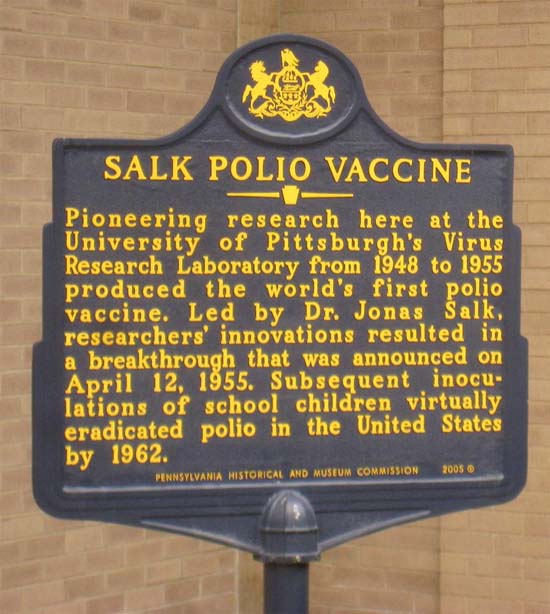

There were many false leads and dead ends in pursuing remedies for polio as there were for COVID-19. Finally, in 1955, when the data from research done by Dr. Jonas Salk and others declared the vaccine to be safe and effective, church bells rang and newspapers across the world rolled out the headline, ‘Victory Over Polio!’

On World Polio Day on October 24, 2019, the World Health Organization announced there were only 94 cases of wild polio in the world. The success of the polio vaccine gave way to the launching of a series of vaccines against the effects of many infectious diseases for the 2nd half of the 20th century.

The global infrastructure that the polio eradication effort put in place is helping to fight other infectious diseases also such as Ebola and Malaria, as well as the coronavirus.

Blows to Vaccine Development for Both Polio and COVID

Harm caused by a vaccine could upset confidence in a public health campaign at a crucial time. This happened for both the polio and COVID vaccines. For polio, it was the Cutter tragedy. Cutter Laboratories, one of the six labs chosen to produce the vaccine, mistakenly sent out vaccines to 200,000 children that contained the active polio virus (not the Salk inactivated virus). As a result, 40,000 got polio from it, 200 were left with varying degrees of paralysis, and 10 died.

Polio vaccinations were temporarily halted in 1955 after the Cutter error. But when the error was pinpointed as the problem, the vaccinations restarted weeks later with renewed quality control. Thus, in a short time in 1955, parents once again lined up their children to get their polio shot. This was an example of the understanding that a mistake had been made and a general acceptance that the risks of polio were a much greater threat than the risks of the vaccine. People were personally invested in the vaccine. The public trust was so important and the global campaign to prevent polio with vaccines was successful, eventually nearly eliminating the disease from the planet.

For COVID, in April of 2020, the Covid-19 vaccine campaign in the US also received a blow to the people’s confidence at a crucial time. It was found that among the 6.8 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, six cases of a serious blood-clotting issue had been recorded and one woman had died. The J&J vaccine was paused. But 10 days later, after a careful review of those cases, immunization with the vaccine resumed with new guidance about what symptoms to look for and how to treat these extremely rare events.

LESSONS FOR TODAY FROM THE POLIO VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

There are lessons to be learned from the polio vaccine effort that can be used for the COVID effort today:

- Trusted volunteers from local communities can provide education on disease, research, and vaccines.

- High-profile individuals recognized by various parts of the population can also get people’s attention. The March of Dimes recruited Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, and Marilyn Monroe. Elvis Presley got vaccinated backstage in 1956 at the Ed Sullivan Show.

- Racism was alive and well in the 1950s and the March of Dimes realized that black children often did not receive the vaccine as quickly as the white children did. So they recruited Sammy Davis, Jr. and Ella Fitzgerald to join the campaign. Black children could also to be found on posters for the March of Dimes.

- The strong, consistent message during the polio years was ‘We're all in this together.’ That same message has been heard today but must also come across much more loudly and clearly when we are asking people to get vaccinated for the good of all.

- Both polio and smallpox never reached natural herd immunity. They were eradicated by vaccines. Vaccines work!

As a virus spreads, it can mutate and take on a new form that can be more infectious and deadly. It is common sense that vaccinating as many people as possible can stop a virus in its tracks. Wearing masks when we cannot social distance properly, washing our hands regularly, and talking to our families, friends, and neighbors about the importance of vaccinations is how we can all do it.

FURTHER LESSONS

The polio vaccine development and distribution process demonstrated how vital it is for the federal government to act in ways deserving of public trust. Government officials offered confusing replies and clumsy explanations about the children that had been harmed by the polio vaccine because of the Cutter debacle and this caused an erosion of the trust in the government and the vaccine. Polls found that by June of 1955, almost half of the parents said they would not have their children take any further vaccine shots even though the full regimen of polio inoculation required 3 doses. In 1958 some drug companies halted production completely and all this led to a startling upsurge in polio in 1959.

Today, with COVID-19 already highly politicized, it is critical to administer an effective vaccine delivery program in a manner that builds trust rather than undermines it. Polls have suggested that a minority of Americans will decline to take any vaccine. The scattered reports of allergic reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine have generated honest and realistic responses from the CDC. For any vaccines that require multiple inoculations such as the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, there has to be a maintenance of trust sufficient to get people back for the follow up dose.

There are, of course, significant differences in the social-political contexts of the era in which the polio vaccine was developed and distributed. and today, including the nature and threat of the two diseases and the technologies of the vaccines. But time and again, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed disconcerting parallels with mistakes made in the past.

In those polio days, however, there was no such thing as an anti-vaxxer. Almost every American knew someone who had been stricken. By the mid-1960s, together with a more easily administered oral vaccine introduced by Dr. Albert Sabin in 1961, polio had been effectively eliminated as a public health menace in the U.S. It exists now only in isolated pockets in the poorest regions of developing nations.

POLIO VACCINATION MANDATES

Today, polio vaccine mandates are in place in every state for children in child care and elementary school. In the US, the IPV (inactivated polio vaccine) is given as a shot while in other countries, the OPV oral polio vaccine is given.

Since 2000, the IPV vaccine has been the only polio vaccine licensed and used in the United States to eliminate the risk of vaccine-derived poliovirus that can occur with OPV.

The CDC recommends that children get four doses, one dose at each of the following ages: 2 months, 4 months, 6 through 18 months, and 4 through 6 years old. These doses can provide up to 99% immunity. Adults who have been vaccinated and travel to countries where polio is prevalent may need to have a booster shot of the polio vaccine.

Vaccination is so very important because the disease still occurs in other parts of the world. It would only take one person with polio traveling from another country to bring polio back to the United States.

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566