PHILLIS WHEATLEY

Phillis Wheatley was the first published African American female poet. She led a short, but extraordinary life filled with spectacular tragedy, unlikely fortune, and international fame. Though she died at just 31 years of age, she left an enduring legacy through her art.

EARLY LIFE

Phillis Wheatley was probably born around 1753. When she was a 7 or 8-year-old child in 1761, she was kidnapped from her home in West Africa (possibly Senegal/Gambia) to be sold as a slave.

There was no record of her birth name when she arrived in Boston on the slave ship Phillis, wrapped in a carpet. Since she was too weak to work in the fields, she was sold as a domestic to Susanna Wheatly, the wife of a prominent Boston merchant and tailor, John Wheatley.

LIFE WITH THE WHEATLEYS

Susanna Wheatley, who named the child after the ship on which she was imprisoned, wanted a lady's maid, but what she got was a prodigy! In just over a year, Phillis could speak and read English. The Wheatleys were stunned at her intellect and decided to tutor her.

She lived a privileged childhood with only light household duties. She even had a private room and took meals with the family. John Wheatley was well known as a progressive throughout New England and his family gave Phillis an unprecedented education for an enslaved person, and one unusual for a woman of any race at that time.

As Phillis grew her literary gifts, the Wheatleys promoted her enthusiastically. When she was 11, she began corresponding with preachers and friends. By the age of 12, she was reading Greek and Latin classics in their original languages, as well as difficult passages from the Bible.

When she was 14, her first poem, 'To the University of Cambridge [Harvard], in New England.’ was published, complete with classical Greek references, a sign of her fine education.

Phillis was very strongly influenced by her readings of the works of Alexander Pope, John Milton, Homer, Horace, and Virgil. This led her to the decision to continue to pursue poetry writing. She believed the power of poetry was immeasurable.

In 1768, Wheatley had written ‘To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,’ praising him for repealing the Stamp Act. As the American Revolution grew in strength, her writing themes expanded to express the ideas of the rebellious colonists.

In 1770, her poetry began to contain Christian themes, when she wrote a poetic tribute to the evangelist, George Whitefield, as well as many other poems dedicated to famous figures.

COURT

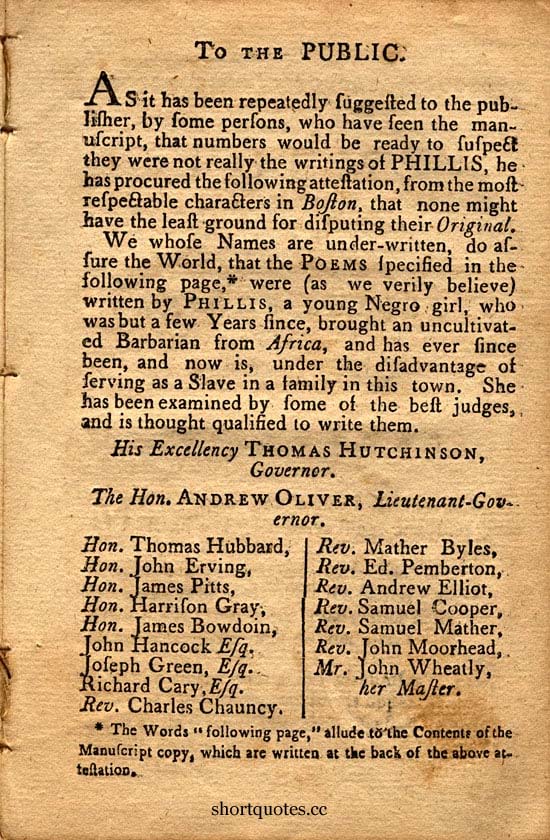

At first, publishers in Boston had declined to publish her poetry. Many colonists doubted that an African slave could be writing such excellent poetry. Phillis was forced to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772.

Several important people from Boston, including John Erving, the Reverend Charles Chancey, John Hancock, Thomas Hutchinson (the Governor of Massachusetts) and Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver examined her and her work and concluded that she had indeed written the poems. They signed a statement corroborating this.

ENGLAND

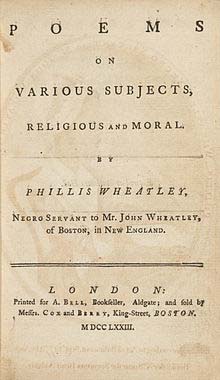

In 1773, Susannah Wheatley sent Phillis to England. Even though Phillis’s fame was growing, Susannah felt she would have a better chance of publishing her poems in England. She sent Phillis, escorted by Susannah’s son, Nathaniel, to London where she met many important figures of the day.

Influential people in London were very interested in her poetry and many became her patrons. Her collected works, ‘Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral' was published in London in 1773. This publication brought Phillis fame in both England and in the American colonies. She included the signed statement from her case in court in the preface of that book.

George Washington praised her work and invited her to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts after receiving a copy of her poem entitled ‘To His Excellency, George Washington.’ She did visit him in 1776. Thomas Paine republished the poem in the Pennsylvania Gazette in April of 1776. A few years later, African American poet Jupiter Hammon praised her work in a poem of his own.

FREEDOM

Unfortunately, shortly after her arrival in London Phillis learned that Susanna Wheatley had become gravely ill. Phillis returned immediately to Boston and in 1774 Susanna died.

Phillis was freed but stayed on with John Wheatley until he died in 1778. Her freedom meant she had lost her patrons and even though she had written a second volume of poems in 1779, she could not get them published. Fortunately, some of her poems from the second volume were later published in pamphlets and newspapers.

MARRIAGE, CHILDREN, and DEATH

In 1778, Phillis Wheatley married John Peters, a shopkeeper. Tragedy visited Phillis again when both of her children died during infancy. A third pregnancy proved fatal for her and the infant she was carrying, and she died in 1784 at the age of 31.

THE POETRY of

PHILLIS WHEATLEY

Wheatley's poetry was patriotic and topical, touching on current affairs, but also suffused with Christian themes. Though her poetry reflected the literature she read, it was based on her personal ideas and beliefs. Her poems were often somber, and a large number consisted of religious, classical, and abstract themes.

Phillis Wheatley rarely referred to her own life in her poems. Here is an example of a poem on slavery, ‘On being brought from Africa to America.’

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic dye.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

CRITIQUES OF THE POETRY OF

PHILLIS WHEATLEY

Many black literary scholars have felt that there is an absence in her poetry of her sense of identity as a black enslaved person. This has been used as an example of Uncle Tom syndrome, a demeaning term for African Americans who give up or hide their ethnic outlook, traits, and practices, in order to be accepted into the mainstream. Many believe that her lack of awareness of her condition of enslavement served to further this syndrome among descendants of Africans in the Americas.

These scholars explain that Phyllis’ upbringing may have created a misconception for her of the relationship between black and white people. This is because the Wheatley family isolated her from other slaves in the home as well as from the enslaved and free black communities.

Other experts say she was the most talented poet of the Revolutionary era. Her writings on slavery expressed the need to recognize the dignity and humanity of African people. Some have also argued that her poems used classical imagery designed to deliver dissident messages to her majority audience, which was white, while arguing for her own freedom as well as those of other enslaved people.

As a freed adult, Phillis had a close friend, an enslaved woman, who introduced her to the African Union Society. Her ties to the African-Americans in New England influenced her life and writing as strongly as Boston’s white elite did.

HONORS

Those who criticize her writing aside, the work of Phillis Wheatley has been considered fundamental to African American literature. She is the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry and the first to make a living from her writing.

Below are some honors commemorating her life and poetry:

- The Boston Women's Memorial is a trio of sculptures on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall between Fairfield Street and Gloucester Street on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts, commemorating the life and work of Phillis Wheatley along with 2 other women. The other 2 women are Abigail Adams, a founder of the United States, the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, and the mother of John Quincy Adams and Lucy Stone, an American orator, abolitionist, and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women.

- Phillis Wheatley is commemorated on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

- The Phyllis Wheatley YWCA is in Washington, D. C.

- The Phillis Wheatley High School is in Houston, Texas.

- The historic Phillis Wheatley School in Jensen Beach, Florida is now the oldest building on the campus of American Legion Post 126.

- A branch of the Richland County Library in Columbia, South Carolina is named for Phillis. This was the first library offering services to black citizens.

- Wheatley Hall at UMass Boston is named for Phillis Wheatley.

- In 1954, the Phillis Wheatley Elementary School in New Orleans opened in Treme, one of the oldest African American neighborhoods.

- In 1930, the Phillis Wheatley Community Center opened in Greenville, South Carolina.

- In 1924, a Community Center opened in Minneapolis, Minnesota with the spelling of Phyllis.

- In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Phillis Wheatley as one of 100 Greatest African Americans.

- In 2012, Robert Morris University named the new building for their School of Communications and Information Sciences after Phillis Wheatley.

- In 2018, Phillis was the subject of a project and play by British-Nigerian writer Ade Solanke. It was entitled 'Phillis in London' and showcased at the Greenwich Book Festival.

- In 2019, at the location in London where her first book was published in September of 1773 a commemorative blue plaque honoring Phillis was unveiled.

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566