ORIGIN OF VACCINATION

You may be surprised to learn that the story of the origin of vaccination that history has relayed to us really amounts to a massive white lie!

The history books tell us that Edward Jenner was a young doctor who, during the smallpox endemic, observed that milkmaids never got the disease and therefore escaped the inevitable face scarring. He theorized that milking cattle exposed the young ladies to cowpox, and it was the cowpox virus that was giving them protection from smallpox.

Jenner tested this hypothesis on a young boy by inoculating him using material from a cowpox pustule. The boy was proven immune from smallpox and voila! the procedure of vaccination was born!

This story can be found on many authoritative websites, even the CDC’s. The PBS NewsHour enhanced it further by reporting that a milkmaid in the English countryside, witnessing an outbreak of smallpox, told Jenner she would never have smallpox because she had contracted cowpox so she would never have a pockmarked face!

Here is the real story of the origin of vaccination:

VARIOLATION and SMALLPOX

The procedure of variolation, which predated Jenner and vaccination by centuries, was used around the world with the hope it would protect against the horrors of smallpox, a very old disease.

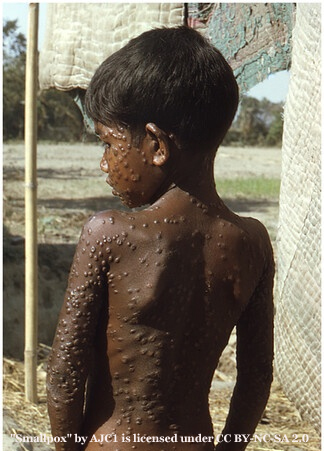

Smallpox is highly infectious and can kill nearly one in three people who catch it. Survivors are often left with pitted scars on their skin, and some can also lose their sight. Traces of its scarring have been found on some thousand-year-old Egyptian mummies!

Our ancestors did not know that smallpox was an infection caused by the variola virus. The word, variola, comes from the Latin that in this context meant ‘mottled’ or a ‘pimple.’ Variolation was known as inoculation or ingrafting and could be found in many areas of the world, even as early as 1549 in China, and possibly for thousands of years in India. The real story behind the origin of variolation or inoculation (ingrafting) has most probably been permanently lost.

The procedure of variolation consisted of taking material from an active smallpox pustule and putting it into another person’s body. This could be by rubbing against a superficial cut made on the arm or ground up pustule material blown into the nose using a long pipe (although this technique could potentially multiply the virus and overwhelm the immune system). The idea was a sensible one. A more localized infection most likely would not kill the recipient but could give lifelong immunity against smallpox. Variolation was much safer than getting the disease itself with its high mortality rate.

The variola virus spread around the world and variolation followed it. When it got to Great Britain, the procedure was popularized by Lady Montagu, the wife of a British ambassador who while living in Constantinople saw that since the country had adopted variolation, smallpox was a relatively harmless disease to the Turks. She had her young son inoculated in Turkey and had her daughter, who had been born in Turkey, inoculated when she returned to Britain. In Britain, she enlisted members of the aristocracy to spread the use of inoculation. Her story can be found here.

ORIGIN OF VACCINATION-

THE REAL STORY

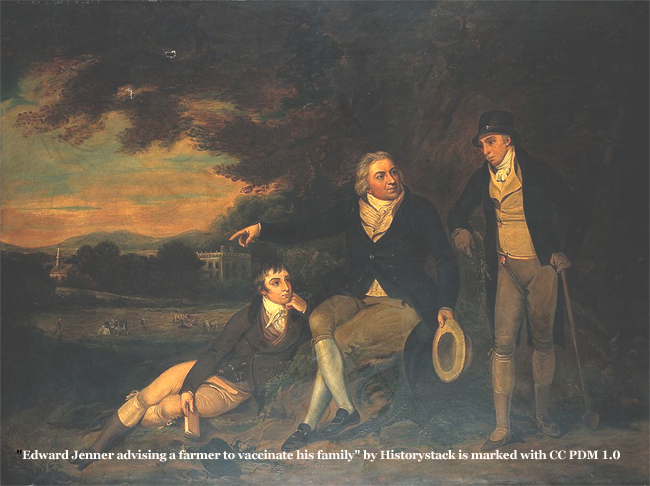

The real story of the origin of vaccination begins in southwest England in an area known as the West Country. It was here that John Fewster, a country doctor, had been inoculating the people of the area against smallpox. He was using an improved version of variolation formulated by 2 other doctors in his practice, Daniel Sutton, and his father.

Fewster found that most people he inoculated would develop a pus-filled blister on their skin. But some people did not show any sign at all that they had been inoculated and Fewster’s curiosity was peaked. While variolating a farmer one day who did not react to the procedure, the farmer told him he had contracted a violent bout of cowpox. Fewster went back to the people who had no reaction to the variolation and found that all had previously had cowpox.

In Fewster’s time, medical conferences did not yet exist, and medical journals were rare. Instead, local doctors would meet and exchange information in informal settings. Fewster relayed his discovery at a meeting where Daniel Ludlow a doctor and his brother Edward, an apothecary, were present. Daniel had a 19-year-old apprentice at the time by the name of Edward Jenner.

Jenner eventually became a house surgeon in London and after many years he returned to the West Country and found that most of the physicians and farmers had spread the discovery that a lack of pustulation after inoculation could be due to a prior exposure to cowpox.

At the time of Jenner’s arrival, Fewster had lost interest in going further with his studies and was fine with the fact that inoculation was safer than getting cowpox. Unfortunately, cowpox did not always provide protection against smallpox. Enter Dr. Edward Jenner.

EDWARD JENNER'S

REAL CONTRIBUTION

As Edward Jenner continued his own work with inoculation, he found that the reason why people exposed to cowpox did not always develop immunity against smallpox was because the word cowpox was being used indiscriminately to refer to three different diseases. The three were a Staphyloccus infection, Milker’s nodes, and an infection by the cowpox virus. He concluded that even though a natural cowpox infection could be dangerous, inoculating people with the cowpox infection in much the same way he was doing with smallpox would be safer than inoculation with smallpox. If the actual cowpox virus was used, not one of the other similar diseases, immunity to smallpox could be obtained.

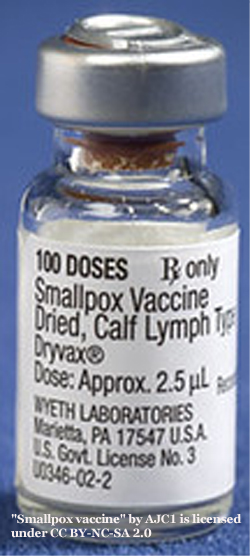

So, where did the milkmaid come in? A milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes, caught cowpox in 1796 in a local outbreak. Jenner took the material from her hand sore and used it to ‘vaccinate’ a healthy 8 year old boy named James Phipps. He then tried to give the boy smallbox twice but James was immune to it. Thus, the crude cowpox ‘vaccine’ had protected him from smallpox. Jenner referred to it as ‘vaccination,’ from the Latin ‘vacca’ for cow.

But Edward Jenner was not the first person to have introduced cowpox material into a human to induce immunity against smallpox. There was Benjamin Jestey, who in 1774 had done it on his family, using a knitting needle and pus from an infected cow. A few others, including Peter Plett, a teacher from Kiel, had also used the procedure.

What made Jenner different from the others was not that he was a pioneer but that he documented his experiments and tried to get them published.

WHY THE LIE?

There was much opposition to the procedure of vaccination as presented by Edward Jenner. Country doctors, used to smallpox inoculation, did not want to switch to a new procedure for which there was initially little evidence. They didn’t think this ‘cowpoxing’ as they called it would give lifelong immunity to smallpox.

Also, unfortunately, Jenner had put forth a strange notion that cowpox came from the infection of the hooves of horses which would mutate when it infected cows. This idea of Jenner’s did not give much credence for Jenner’s ‘vaccination’ procedure to be adopted by the doctors.

Edward Jenner’s reputation needed to be rehabilitated after his death and it was his first biographer, John Baron, who created the milkmaid myth to reduce the role of Fewster and elevate the role of Jenner in the invention of vaccination. Instead, as the story goes, the brilliant discovery that exposure to cowpox could immunize a person against smallpox had come about because of Jenner’s observation of beautiful milkmaids!

There are some real problems with this story. First, milkmaids were not renowned for their beauty. Secondly, milking of cows was not limited to girls in the 1700s. Not every milkmaid was exposed to both smallpox and cowpox either. But it was certainly a nice story that simplified a messy history and elevated Dr. Edward Jenner, a historical figure, to the status of a hero by passing on yet another origin myth to the world.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

Vaccines have proven themselves over time to be a much-needed tool for public health. But vaccines were not the creation of a single man. Jenner and many of his contemporaries experimented with vaccines but the procedure has been perfected by countless researchers over centuries. The most amazing result is that smallpox was eradicated globally in 1980 due to the smallpox vaccine!

We must remember that few people deserve all the credit for their discoveries. This is especially true for women researchers of the past, especially black women, so many who never received credit for their work but without whom so many scientific discoveries could not have happened. Hopefully, an expose of the milkmaid smallpox myth will eventually show a more accurate story of the origin of vaccination.

Please note: Some information for this article was used with permission from McGill University Office of Science and Society.

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566