NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH

November is Native American Heritage Month. Here are some of the famous leaders whose names still ring through the places, people, and things in America:

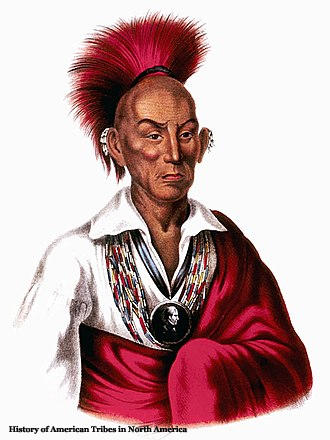

BLACK HAWK

Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak) was born in 1767 in what is now the midwestern part of the US. His village of Sukenuk was on the Rock River which is present-day Rock Island, Illinois. He became a band leader and fierce warrior of the Sauk Native American tribe.

Blackhawk was not a hereditary chief but did inherit an important historic sacred bundle from his medicine man father. He had to earn his status as a war leader and warrior by his actions--leading large numbers of raiding and war parties over many years.

He was very critical of what he considered to be unfair treaties enacted by the US and he sided with the British in the War of 1812 in hopes of pushing white American settlers away from Sauk territory. Later he led a band of Sauk and Fox warriors, known as the British Band, against white settlers in Illinois and present-day Wisconsin during the 1832 Black Hawk War.

Eventually, he was captured by US forces and taken to the Eastern US, where he and other war leaders were taken on a tour of several cities as ordered by President Andrew Jackson. The men were taken by steamboat, carriage, and railroad, and met with large crowds wherever they went. Jackson wanted them to be impressed with the power of the United States.

Shortly before being released from custody, Black Hawk told his story to an interpreter. Aided also by a newspaper reporter, he published the Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk, Embracing the Traditions of his Nation in 1833 in Cincinnati, Ohio. The book was one of the first Native American autobiographies to be published in the US. It became an immediate bestseller and has gone through several editions. There is some concern that the final revision of the book may have been edited with potential readers in mind rather than as an accurate record of events relayed by Black Hawk to the interpreter and the newspaper reporter.

Black Hawk died in 1838 in what is now southeastern Iowa.

COCHISE

Cochise, an Apache Chief also known as Shikashe or Adatlichi in Apache, was born in 1805 in the area that is now the northern region of Sonora, Mexico, New Mexico, and Arizona. The Apache people had settled in that region sometime before the arrival of the European explorers and colonists.

Cochise's name meant 'having the quality or strength of an oak.' He became a key war leader during the Apache Wars as principal chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache. He led uprisings against the US government that began in 1861 and persisted until a peace treaty between Cochise and the US government was enacted in 1872.

During the uprisings, the US government found it very difficult to pursue Cochise and capture him. He knew the land well and his people were very effective warriors. However, eventually, the constant running and fighting started to take their toll on the Chiricahua Apache.

The US was also losing too many soldiers and looked for another possible solution to the Cochise problem. Their strategy shifted to relocating him and his people to a reservation. He was repeatedly asked to meet and discuss this, but he would always refuse because of the confinement, poor conditions, and poor treatment of the treatment of natives on reservations.

Finally, in 1872, Cochise was approached by General Howard and Tom Jeffords, an Army scout. The ensuing negotiations gave Cochise a reservation for his people that spanned much of modern-day Cochise County in southeast Arizona. This was something Cochise could live with, and he did indeed live on the reservation for 2 years until his death in 1874.

The reservation lasted just 4 years until 1876 when the US moved the Chiricahua and some other Apache bands to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. This was in response to public outcry after some white settlers were killed.

Unfortunately, the Indians hated the desert environment of San Carlos and often left the reservation, sometimes raiding neighboring settlers. Unrest between the Indians and the settlers extended the Apache Wars, which continued for many years after Cochise’s death.

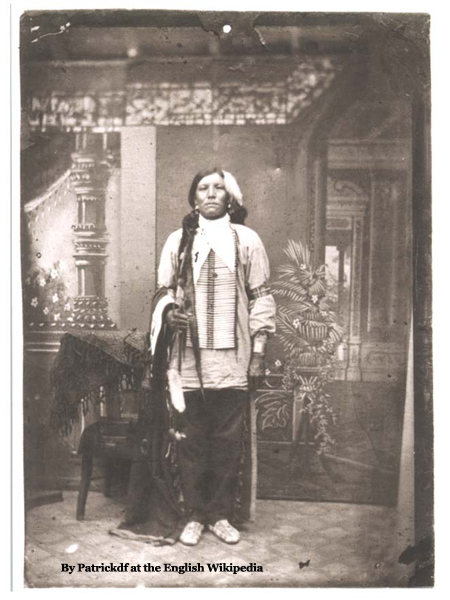

CRAZY HORSE

Crazy Horse or Tasunke Witco, was born a member of the Oglala Lakota around 1840 in the Black Hills of South Dakota. His father was a shaman (also named Crazy Horse) and his mother, a member of the Brule Sioux.

As soon as he was old enough, Crazy Horse set out on the Vision Quest or Hanbleceya (crying for a vision or to pray for a spiritual experience), one of the important rites of passage to a Lakota warrior. He went alone into the hills. There he fasted for days and cried to the spirits for a dream.

During that time, he

had a vision of an unadorned horseman who directed him to present himself in

the same way, with no more than one feather and never a war bonnet. He was also

told to toss dust over his horse before entering battle and to place a stone

behind his ear and directed to never take anything for himself. He followed the instructions in that dream for his entire life.

By the time he was in his mid-teens, Crazy Horse was a full-fledged warrior and exhibited bravery and prowess in battle. In 1876, he led a band of Lakota warriors against Custer’s Seventh US Cavalry battalion. This was the Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as Custer’s Last Stand. Custer and all his battalion died and only 32 Indians were killed. Crazy Horse was also joined by Sitting Bull and his warriors at the battle.

Crazy Horse had become an adult during a time when cultures clashed, land became an issue of deadly contention, and traditional Native ways were threatened and oppressed. After the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the United States Government sent scouts to round up any Northern Plains tribes who resisted. Many Indian Nations were forced to move across the country, always followed by soldiers, until starvation or exposure would force them to surrender.

In 1877, under a flag of truce, Crazy Horse surrendered at Fort Robinson in Nebraska and attempted to negotiate with the US Government. Unfortunately, there was a breakdown in negotiations because the translator incorrectly translated what Crazy Horse said and he was escorted toward the jail. When he realized the officers were planning on imprisoning him, he struggled and drew his knife. An infantry guard was able to mortally wound crazy Horse, and he died shortly afterward.

It is a well-known fact that Crazy Horse refused to have his picture or likeness taken. Crazy Horse lived under the assumption that by taking a picture a part of his soul would be taken, and his life would be shortened. Likenesses of Crazy Horse had to be developed by descriptions from survivors of the Battle of the Little Bighorn and other contemporaries of Crazy Horse the man.

GERONIMO

Geronimo or Goyathlay was born in 1829 in No-Doyohn Canyon, Mexico and became a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Apache tribe. He defended his people against the encroachment of the US on their tribal lands for over 25 years.

From 1850 to 1886, he joined with members of 3 other Chiricahua Apache bands to carry out numerous raids. Geronimo's raids and related combat actions were a part of the prolonged period of the Apache-United States conflict, which started with American settlement in Apache lands following the end of the war with Mexico in 1848.

While Geronimo was well known and a superb leader in raiding and warfare, he was not a chief of the Chiricahua. However, at any one time, he would be in command of about 30 to 50 Apache.

1876 to 1886 was the final period of conflict for Geronimo. During that time, he had surrendered 3 times and accepted life on the Apache reservations in Arizona. But like other Apache, reservation life was confining to the free-moving Apache people, and they resented restriction on their customary way of life. In 1886, following Geronimo’s third reservation breakout, he surrendered for the last time and the US government treated him as a prisoner of war.

While holding him as a prisoner, the US displayed him at various events capitalizing on his fame among non-Indians. These displays provided him with an opportunity to make some money. He sold pictures of himself, bows, arrows, buttons off his shirt, and even his hat.

In 1898, Geronimo was exhibited at the Trans-Mississippi and International exhibition in Omaha, Nebraska. These exhibitions were so successful, he became a frequent visitor to fairs, exhibitions, and other public functions.

In 1905, the Indian Office provided Geronimo for the inaugural parade for President Theodore Roosevelt. Later that year, the Indian Office took him to Texas, where he shot a buffalo in a staged roundup. He was escorted to the event by soldiers since he was still a prisoner. Apparently, those who witnessed the buffalo hunt were unaware that Geronimo’s people were not buffalo hunters!

Geronimo died in 1909, as a prisoner of war.

PONTIAC

Ottawa war Chief Pontiac was born in 1720 in the Great Lakes Region of the US and was also known as Obwandiyag. He became the chief of the Ottawa Indians in 1755 and became head of the Council of Three, an intertribal group consisting of the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibwa people.

The three tribes had coexisted well with the French. Pontiac had aligned his allegiance with the French and after the British victory in the French and Indian War, he and the Indians in the region became dissatisfied with the policies of the British. They were treated so differently from how they had been treated by the French. Most important to the Indians was the fact that the British no longer felt they had to ask permission from the Indians to build forts, and they continued to build them. This did not sit well with Pontiac or the others. Some Indian people felt the British intended to destroy or suppress them.

A revolt led by Pontiac and 300 followers in May of 1763 attempted to take Fort Detroit by surprise. The plan was foiled, so Pontiac laid siege to the fort where he was joined by more than 900 warriors from a half-dozen tribes. This became known as Pontiac’s War. In July of 1763, Pontiac defeated a British detachment at the Battle of Bloody Run, but he was never able to capture the fort itself.

In October of 1763, Pontiac withdrew to the

Illinois Country but his efforts contributed to the British Crown’s issuance of

the Proclamation of 1763. King George III

declared all lands west of the Appalachian Divide off-limits to colonial settlers.

Pontiac continued to encourage various tribal leaders to fight against the British. The British sought to end the conflicts and in July of 1766, the Brtitish made peace with Pontiac. This aroused much resentment among other tribal leaders who ostracized him for claiming he had greater authority than he actually possessed.

In the years following Pontiac’s War, the British actually increased their frontier presence. Unfortunately, this was the opposite of Pontiac’s original intentions. Pontiac’s early successes at rebellion and his ambition and determination gave him a temporary prominence and the British assumed that chiefs were able to hold more authority than they usually did.

In 1768, Pontiac was forced to leave his Ottawa village and relocate to what is now western Tippecanoe County, Indiana. There he was assassinated in 1769 by a Peoria warrior, although the reason behind the assassination is not clear. His burial place is possibly in St. Louis. In 1900, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a commemorative plaque in a corridor of the Southern Hotel in St. Louis, said to be near Pontiac’s burial place.

Sacagawea

Sacagawea (Sacajawea, Sakakawea) was a Native American Shoshone woman born

in 1788 and most well-known for accompanying Lewis and Clark during their Corps

of Discovery of the 828,000 square miles in the Western United States acquired by the US with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

In April of 1805, 17 year old, pregnant Sacagawea, her husband, and their infant son left with the Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore the newly acquired area. At first she was just considered to be her husband’s wife who possessed specific native language interpretation abilities. But Sacagawea soon became essential to the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. She was very knowledgeable about land survival and she helped supply the Corps with food foraged from the wild roots, berries, and other edibles available. She was essential in helping to establish cultural contacts with Native American populations along the way as well. She also appeared calm and collected in crises. She was responsible for saving Clark’s journals, instruments, and other supplies when one of their boats almost capsized.

In August of 1805, west of the Continental Divide, the expedition needed to secure horses from the Shoshone tribe. Sacagawea was delighted to be reunited with her brother, Cameahwait, who then provided horses and guides to the expedition through the Bitterroot Mountains and through the Salmon River country to the Clearwater and Columbia Rivers. In November of 1805, the Corps reached the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

Sacagawea’s skill, determination, courage, and insight on the Expedition were an outstanding achievement. In June of 1998 the Dollar Coin Design Advisory Community, supported by members of the public recommended creating a dollar coin with the image of Sacagawea. It was actually the first time in the history of the US Mint that the public played such an important role in choosing the final design of a coin.

The Sacagawea Dollar coin was first released for circulation on January 27, 2000. The reverse of the coin featured a soaring eagle surrounded by seventeen stars representing the union members in 1804 and this design was used from 2000 until 2008. Starting in 2009, the reverse design has been changed every year and depicts different characteristics of Native American culture.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association of the early 20th century adopted Sacagawea as a symbol of women's worth and independence. They erected several statues and plaques in her memory and did much to spread the story of her accomplishments.

The later life and exact date of Sacagewea’s death are not well-documented.

SEQUOYAH

Sequoyah or Sequoiah, also known as Sogwali, George Guess, Guest or Gist grew up in Tuskegee, Tennessee with his mother. He was born in 1770 to a Cherokee mother and a white fur-trader father who left the family when Sequoyah was very young. He and his mother ran a trading post that they had opened together. After his mother died in 1800, he continued to run the trading post and taught himself to make jewelry. Shortly thereafter he was introduced to silver smithing and was able to establish his trade.

Sequoyah never learned to read or write English, but he understood that the ability to communicate through the written word gave power to the white people and he saw it would be a critical step for the Cherokee people.

He decided to develop a Cherokee writing system. It took him about 12 years to complete the syllabary (a set of written characters representing syllables which can serve the purpose of an alphabet). His syllabary had 86 symbols, each representing a sound in the language.

Sequoyah was also among the many Cherokees who enlisted in the US armed forces during the War of 1812. When Sequoyah saw white warriors writing letters home, he was even more convinced that his writing system was going to help his people.

When the syllabary was ready, he introduced it to the Cherokees but had to convince them it would be useful. The leaders of the Cherokees eventually did adopt Sequoyah’s writing system in 1821. As a result, the first Indian newspaper appeared shortly thereafter, and the Bible was translated into Cherokee.

Sequoyah moved to Oklahoma in 1828 and passed away in 1843.

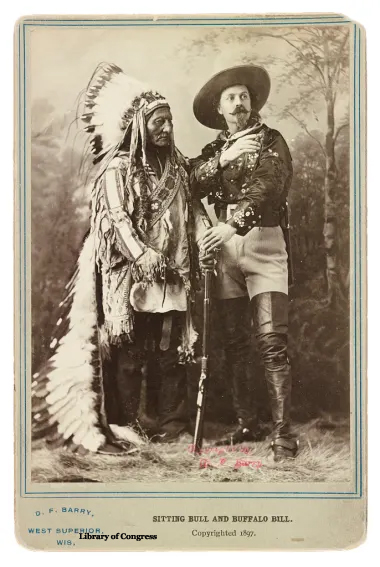

SITTING BULL

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lokota holy man who led his people during years of resistance against US government policies. He was born in 1831 near Grand River, Dakota territory in what is South Dakota today. He was the son of Returns-Again, a renowned Sioux warrior who named his son 'Jumping Badger' at birth. The young boy killed his first buffalo at age 10 and by 14 had joined his father and uncle on a raid of a Crow camp. After the raid, his father renamed him Tatanka Yotanka, or Sitting Bull, for his bravery.

Sitting Bull eventually joined the Strong Heart warrior society and the Silent Eaters, a group that ensured the welfare of the tribe. He led the expansion of Sioux hunting grounds into westward territories previously inhabited by the Assiniboine, Crow, and Shoshone, among others.

Sitting Bull's experience with the US government convinced him that he would never sign a treaty that would force his people onto a reservation. This won him many followers and around 1869, he was made supreme leader of the autonomous bands of Lakota Sioux. Members of the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes soon joined him.

Sitting Bull was known as a chief who united the Sioux tribes of the American Great Plains to fight against the white settlers taking their tribal land. In 1868, the Fort Laramie Treaty granted the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota to the Sioux, but when gold was discovered there in 1874, the U.S. government ignored the treaty and began to remove native tribes from their land by force.

Defiant, Sitting Bull refused to back down. He mustered a force that

included the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux and faced off against General George

Crook on June 17, 1876, winning victory in the Battle of the Rosebud. From

there, his forces moved to the valley of the Little Bighorn. where he was also joined by Crazy Horse.

Just before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull had a vision in which he saw many soldiers, as thick as grasshoppers, falling upside down into the Lakota camp. His people took this as an omen of a major victory in which many soldiers would be killed. About three weeks later, the confederated Lakota tribes with the Northern Cheyenne defeated the 7th Cavalry under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer on June 25, 1876, annihilating Custer's battalion and seeming to bear out Sitting Bull's prophetic vision.

In the wake of The Battle of Little Bighorn, the incensed U.S. government redoubled their efforts to hunt down the Sioux. At the same time, the encroachment of white settlers on traditionally Indian lands greatly reduced the buffalo population that the Sioux depended on for survival. In May 1877, Sitting Bull led his people to safety in Canada. He remained there until 1881.

With food and resources scarce, Sitting Bull finally surrendered to the U.S. Army on July 20, 1881, in exchange for amnesty for his people. He was a prisoner of war in South Dakota’s Fort Randall for two years before being moved to Standing Rock Reservation.

Sitting Bull was occasionally permitted to travel, and it was on one of his trips outside the reservation that he struck up a friendship with sharpshooter Annie Oakley after seeing her perform in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1884.

In 1885, Sitting Bull joined Oakley in performing in Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. Sitting Bull rode in the show’s opening act, signed autographs, and even met President Grover Cleveland.

After working as a performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. Standing Rock Reservation had become the center of controversy when the Ghost Dance Movement started gaining traction. The followers of this movement believed that deceased tribe members would rise from the dead along with killed buffalo while all white people would disappear. Worried that the influential Sitting Bull would join the movement and incite rebellion, Indian police ordered his arrest.

During an ensuing struggle between Sitting Bull's followers and the agency police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by the police after they were fired upon by Sitting Bull's supporters. Sitting Bull died instantly.

After the death of Sitting Bull, the army massacred 150 Sioux at Wounded Knee, the final fight between federal troops and the Sioux.

SQUANTO

Squanto, also known as Tisquantum, lived from 1585 to1622. He was originally a member of the Pawtuxet tribe, a branch of the Wampanoag Confederacy, located in what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. He had been kidnapped and sold into slavery in Malaga, Spain a decade before the Pilgrims landed in 1620. In Spain he was bought by a Spanish monk who apparently treated him well, taught him the Christian faith and then freed him. Squanto eventually found his way to England and worked in the stables of John Slaney. It was in England where he either learned or improved whatever English he knew. Slaney understood Squanto’s desire to return home and promised to put him on a ship bound for America as soon as one could be found.

When Squanto finally returned home, he found his entire tribe had died, most likely from smallpox brought by early English settlers. The Wampanoag tribe, located close to the Pilgrim colony of Plymouth, captured Squanto and held him prisoner. The tribe and the Pilgrims were very wary of each other. It was commonly known that Indians that attempted to befriend the English in the past had been taken captive themselves.

One of the members of the tribe suggested that Squanto, because of his knowledge of the English language, could be used as an interpreter to negotiate an alliance with the Pilgrims. In this alliance was the promise not to harm each other and that they would aid each other in the event of an attack from another tribe.

Squanto actually became a member of the Pilgrim colony. It is thought he was probably present at the first Thanksgiving. He introduced the settlers to the fur trade and taught them how to sow and fertilize native crops such as corn. This education proved essential, since most of the seeds the Pilgrims had brought with them from England had failed.

Because Squanto could speak English well, he was also asked by Governor William Bradford to serve as his ambassador to the Indian tribes. As food shortages in the colony worsened, the Governor commissioned Squanto to pilot a ship of settlers on a trading expedition around Cape Cod. During that voyage, Squanto became mortally ill. Bradford stayed with him for several days until he died. When Squanto died in 1622, he bequeathed his belongings to the Pilgrim colony

Some historians question Squanto’s actual motives for helping the Pilgrims. There is some evidence he may have used his abilities to gain power for himself. Nonetheless, children are taught in school to remember him as the kindly Indian who befriended the Pilgrims and helped them to survive in their new environment. And there can be no question that he certainly can be remembered as an extraordinary translator, guide, and advisor to the early settlers.

TECUMSEH

Tecumseh was born a Shawnee in 1768 in what is now present-day Ohio. He grew up during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War. He became the primary leader of a large Native American confederacy in the early 19th century. Tecumseh was known as a strong and eloquent orator who promoted tribal unity. He was very involved in warfare. He envisioned the establishment of an independent Native American nation and he worked to recruit additional members to his tribal confederacy from the Southern US. States.

Tecumseh was ambitious and willing to make significant sacrifices to repel settlers from Native American lands in the Old Northwest Territory. In 1808, Tecumseh with his brother founded the Native American village (called Prophetstown by the whites) north of present-day Lafayette, Indiana. This town grew into a large, multi-tribal community and was a central point in Tecumseh’s political and military alliance.

Tecumseh was never successful in stopping the US government from overrunning Indian lands. Although he remained the military leader of the pan-Native American confederation, he was never able to see his dream to enlarge the Native American alliance fulfilled.

Tecumseh was killed in the War of 1812 during the Battle of the Thames in October of 1813. His death caused the pan-Native American alliance to collapse. Within a few years, the remaining tribal lands in the Old Northwest were ceded to the US government and opened for new settlement. Most of the Native Americans eventually moved west across the Mississippi River.

Top of Native American Heritage Month

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566

ABC

Carpet & Rug

Spotting Guide

Learn how to remove spots with ordinary household solutions

Sign up below to gain access to your complementary Spotting Guide from ABC.

Registering your email address guarantees you will be notified whenever discount savings coupons become available.

Did you know that our ABC Responsible Care Spotter can get those pesky spots out of your carpet and rugs and will work equally as well on your clothes and upholstery?

Stop by our office and pick one up. They are $5.00 + Tax but if you have carpets or upholstery cleaned in your home or business, just request a free one from your Technician.

And don't forget to fill out the form above to download your free ABC Spotting Guide!

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

is a FOUNDING MEMBER of the

Association

of Rug Care Specialists.

"To Teach, Cultivate and Advance the Art and Science

of Rug Care"

GIVE THE

GIFT OF CLEAN!

Why not think 'outside the box' and give

a Gift Certificate for professional carpet, upholstery, or tile

& grout cleaning from ABC for any special occasion!

Does a special person have a favorite area rug or oriental rug that needs cleaning or repair? Just give us a call. You'll make their day!

Bring in the mats from a car and we'll clean them as well.

Contact

us if you live in the Ithaca, NY or surrounding areas and we will

tailor a special gift certificate just for you for any Special Occasion.

The Standard of Excellence