HEART-LUNG MACHINES

Heart-Lung Machines save hundreds of thousands of lives each year.

For February, Heart Health Month, here is the amazing story of the first Heart-Lung

machine and its inventor, Dr. John H. Gibbon Jr.

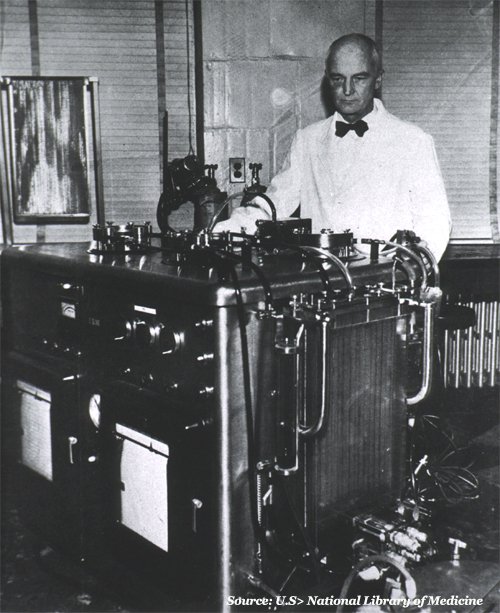

FIRST HEART-LUNG MACHINE

Almost sixty-seven years have passed since the first successful heart-lung machine was used in surgery. Unfortunately, generations of people have little memory of what a diagnosis of heart problems once meant.

In those days, there were no real therapies for heart problems. A patient could possibly have an operation, but it wasn't likely that he or she would survive it.

Then, on May 6, 1953, an 18-year-old woman survived open heart surgery and recovered. Her surgery was an experiment 23 years in the making and the result of the singular vision and struggle of Dr. John H. Gibbon, Jr.

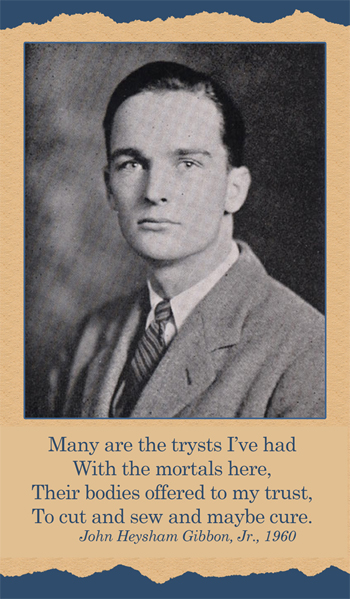

DR. JOHN H GIBBON, JR.

The struggle began in 1931 when, as a surgical resident, Gibbon was assigned to monitor a young woman who, two weeks after surgery, developed a blood clot that went to the heart. During a long night, Gibbon watched as she progressively became worse. Her heart and lungs could no longer provide oxygen to her blood.

That morning, Gibbon observed as a surgeon attempted to remove the blood clot during open-heart surgery. The operation was an act of pure desperation. Open heart surgery prior to 1953 could occur only two ways, either by placing the patient into a hypothermic freeze, or by stopping the heart (and respiration) and working fast.

Surgeons could make repairs in six minutes or so, but patients rarely survived. Prior to 1953, no patient in the U.S. had ever been known to survive the removal of blood clots and neither did the sick young woman on the operating table that day in 1931.

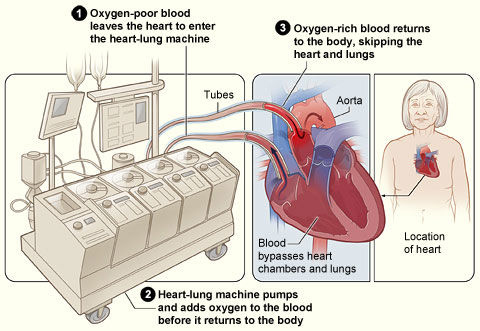

But in that moment, Gibbon had an insight: Blood must be

circulated and oxygenated by a machine outside the body while the surgeon

worked inside the body. But what would serve as the pump? How would you provide

the blood to the patient?

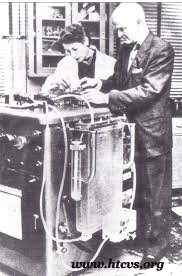

During the next 23 years, Gibbon and his wife/assistant worked on the idea, solving all the major problems associated with using a mechanical pump to bypass the heart. They had no big government grants but unfortunately, they had plenty of opponents and naysayers.

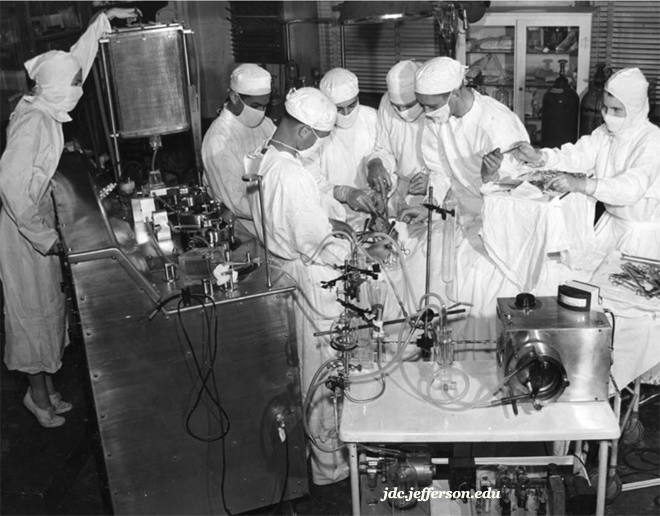

Then on that day in May of 1953, at the Jefferson Medical College Hospital, Gibbon tried out his new bypass machine, operating on an 18-year-old woman. Assistants watched in awe as the impossible happened and the patient lived through a once-impossible surgery. She was connected to the device for three-quarters of an hour and for 26 crucial minutes, the patient totally depended upon the machine’s artificial cardiac and respiratory functions.

Following the operation, Dr. Gibbon told his biographer he felt exhilaration, relief, and joy. He was so overwhelmed that for the first time in his life he couldn’t even sit down to write down his own operation notes. Another doctor had to supply the notes.

Dr. Gibbon went on to perform four more operations, all on children, but all the patients died. After those four failures, he declared a moratorium on the procedure. He never again went back to heart surgery.

HEART SURGERY

THOUGH THE YEARS

TO THE PRESENT

Happily, there were doctors who made history in the field of heart surgery who took Gibbon’s idea and made it work: Clarence Dennis of Downstate University in Brooklyn; John Kirklin of the Mayo Clinic; and C. Walton Lillehei (known as The Father of Open Heart Surgery) at the University of Minnesota.

The stunning truth is that in 1953, nearly 100 percent of the patients died in open heart surgery and today more than 98 percent thrive.

In the period from 1953 through today, an entire category of lifesaving medicine developed, sparked by the lonely efforts of one doctor. This type of surgery, using much slenderized modern versions of Dr. Gibbon's basic system, has since become commonplace and is now routinely performed on infants and children born with severe heart defects.

The

heart‐lung machine is also used in surgery on adults to repair heart

valves damaged by rheumatic fever, to restore the heart's circulatory system in

the coronary bypass operation and to perform heart transplant operations.

Over 250,000 heart valve replacements are done every year and over 98 percent of those patients recover. Some hospitals have reported they have never lost a heart valve patient on the operating table!

John H. Gibbon, Jr., the descendant of four generations of doctors, died in 1973 of a heart attack.

Dr. OZ VIDEO OF HEART SURGERY IN 2012 USING HEART-LUNG MACHINE

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566