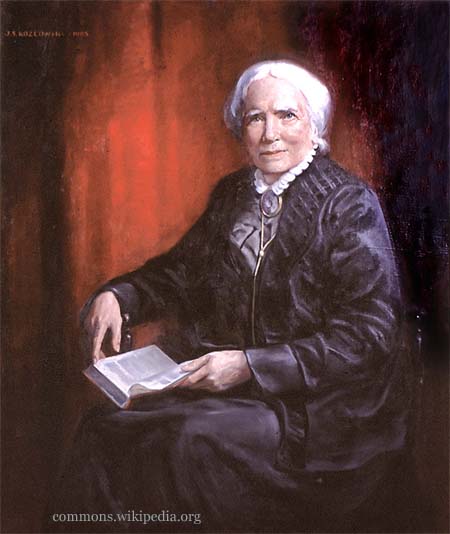

ELIZABETH BLACKWELL

Elizabeth Blackwell, born in 1821 in England, is most remembered as the first fully accredited female doctor in the United States. But she also played a very important role, both in the US and the UK as a social awareness and moral reformer. She was a devout Christian and an abolitionist as well as a staunch pioneer in promoting education for women in medicine. With her sister, Emily, she founded the first medical school for women.

EARLY LIFE

ENGLAND to NEW YORK to OHIO

Elizabeth was one of 9 children-- two older sisters, 2 younger sisters and 4 younger brothers. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, was a successful sugar refiner in Bristol, England. The sugar refinery was eventually destroyed by fire and when Elizabeth was just 11 years old, she and her family emigrated to New York City.

In New York, Elizabeth’s father was actively involved in abolitionist work. At the dinner table, issues of women’s rights, slavery, and child labor were regularly discussed.

Samuel Blackwell’s attitude towards the education of his children was unusual for the time and included the belief that each child should be given the opportunity for unlimited development of their talents and gifts, even his girls. He did not agree with the notion, then popular, that a woman’s place was in the home or as a schoolteacher. Young Elizabeth Blackwell not only had a governess but private tutors as well.

A few years after moving to New York, the family moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. When Elizabeth was 17 her father died, leaving the family with very little money.

EARLY ADULTHOOD

To find a source of income for the family, Elizabeth and her sisters, Anna and Marian, started a school in 1838. It was called ‘The Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies.’ The sisters taught many subjects there as well as charging for tuition and room and board.

The school lasted until 1842 when it was closed after Blackwell started regularly attending the Unitarian Church where she was introduced to the idea of transcendentalism. Repercussions from the conservative Cincinnati community resulted in the academy losing too many pupils. Blackwell began teaching private pupils after the school closed.

While attending the Unitarian Church, Blackwell’s interests in education and reform were renewed. She also studied art, wrote short stories, and attended lectures as well as various religious services in all denominations. Women’s rights had also become a very important concern for her.

In 1844, Elizabeth secured a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky. She found the accommodations and the school lacking and it was here that she had her first experience with the realities of slavery. After only 6 months on this job, she returned to Cincinnati to find a better and more stimulating way to spend her life.

INTEREST IN MEDICINE

Early on in her life, Elizabeth had not been interested in a career in medicine. However, after her experiences with teaching to support her family, she found that the teaching occupation was not a good match for her. Her interest in medicine was sparked after a friend fell ill and let her know that if she had had a female doctor care for her, she might not have suffered so much.

Elizabeth decided she would apply to a medical school. She was able to secure a job teaching music in Asheville, North Carolina to save money for medical school expenses. In Asheville, she obtained lodging with Reverend John Dickson who had been a physician before he became a clergyman. He approved of her career aspirations and allowed her to study the medical books in his library.

Elizabeth’s greatest desire was to be accepted into one of the Philadelphia medical schools. In 1847, she left North Carolina for Philadelphia and New York to personally investigate her opportunities for medical study.

APPLYING TO MEDICAL SCHOOLS

Upon

arriving in Philadelphia, Blackwell boarded with one doctor and studied anatomy

privately with another. Unfortunately, it appeared she was not welcome into any medical

school. It was recommended that she go to Paris to study or disguise herself as

a man to study medicine. The reasons given for her rejection were that she was

a woman and therefore must be intellectually inferior, and she also might be

competition if she showed that she could actually meet the medical school

standards.

Blackwell applied to numerous medical schools and was rejected from each one. True to her nature, she did not give up until she was finally accepted to Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York, originally a separate department of Geneva College, now known as Hobart and William Smith Colleges. She was accepted by the dean and faculty only because as a joke they put her acceptance up to a student vote with the admonition that one dissenting vote would be all it would take to reject her. To their surprise, all 150 male students voted for her matriculation. Thus, in 1847, she became the first woman to attend medical school in the United States.

MEDICAL SCHOOL EDUCATION

The people of Geneva did not fully accept her, and she felt uncomfortable at first. In the summers between her terms, she returned to Philadelphia and applied for medical positions in the area to gain clinical experience.

She was able to secure a position at the Blockley Almshouse, later known as Philadelphia General Hospital. This was a charity hospital and poorhouse located in West Philadelphia and was the first government sponsored care of the poor institution in America. It offered an infirmary and hospital for the sick and insane, besides housing and feeding the impoverished. It was there that she became appalled by the syphilitic ward and patients afflicted with typhus.

Her graduation thesis on typhoid fever was published in 1849 and was the first medical article published by a female student from the United States. It concluded that physical health is linked with socio-moral stability. The medical community, however, felt her perspective of empathy and sensitivity to human suffering, as well as her strong advocacy for economic and social justice was because she was feminine. Nonetheless, this work foreshadowed her later reform work.

MEDICAL STUDIES IN EUROPE

After graduation In 1849, Blackwell decided to continue her studies in Europe. She first went to Britain and then Paris where she was rejected by many hospitals because she was female. However, after acquiring a position at a hospital as a student midwife, not a physician, she gained much clinical medical experience. Paul Dubois, the foremost obstetrician in his day, voiced his opinion that she would make the best obstetrician in the US, male or female.

Unfortunately, her hopes to become a surgeon were derailed when she accidentally got contaminated fluid into her own eyes and lost the sight in her left eye requiring its surgical extraction.

After she recovered, she returned in 1851 to New York City with the hope of establishing her own practice, since she felt the prejudice against women in medicine was not as strong there.

NEW YORK CITY

In New York City, Blackwell continued to be faced with adversity. Her practice didn’t do well at first but again, she forged ahead. She began delivering lectures in 1852 and published a volume about preparation of young women for motherhood and the physical and mental development of girls.

In 1853, she established a small dispensary and took a Polish woman pursuing a medical education under her wing. Along with this woman and Blackwell’s sister, Emily (who had also obtained a medical degree), they expanded her original dispensary into the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. The board of trustees, the executive committee, and the attending physicians were women. The institution also served as an important nurses' training facility, especially during the Civil War.

Blackwell visited Britain many times to raise funds and to try to establish a parallel infirmary project there. While in London she mentored Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who later, in 1865, became the first woman doctor in England.

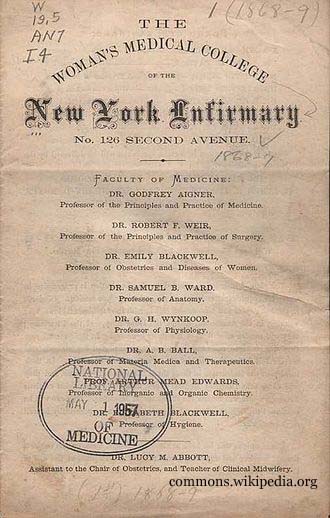

Although the parallel project fell through, in 1868, a medical college for women adjunct to the infirmary in New York City was established. It incorporated her innovative ideas about medical education which included a four year (not 2 year) training period with extensive clinical training.

RETIREMENT FROM

MEDICAL CAREER

Elizabeth Blackwell was a very strong-willed woman and could be very harsh in her criticism of others, especially other women. She did not get along well with her sisters Anna and Emily or with the women physicians she had mentored after they established themselves. She was very assertive and found it difficult to play a subordinate role.

A serious rift occurred between Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell and Elizabeth left for London again in 1869 to try to establish medical education for women there. In 1874, she established a women’s medical school in London. It opened as the London School of Medicine for Women.

In 1877, she resigned from her position due to hostility and loss of authority and officially retired from her medical career.

REFORM MOVEMENTS

From 1880 to 1895 Blackwell was interested in a great number of reform movements. Some of these included moral reform, sexual purity, hygiene and medical education, preventive medicine, sanitation, eugenics, Christian socialism, family planning, women’s rights, medical ethics, etc. She was also strongly antivivisection (surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure.)

None of her interests came to fruition. This was because all her reform work was based on her very elusive and ultimately unattainable goal of evangelical moral perfection.

PERSONAL LIFE and LATER YEARS

None of the Blackwell sisters married. In 1856, during the time Elizabeth was establishing the New York Infirmary, she had adopted an Irish orphan named Katherine ‘Kitty’ Barry. She was lonely but also in need of domestic help, so Barry served as a daughter and a servant. Barry spent the rest of her life with Elizabeth.

In her later years, Elizabeth was still relatively active. In 1895 she published her autobiography ‘Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women’ but it was not successful.

After 1895, she slowly left her public reform interests and spent more time traveling. Up until her death, she worked in a practice in Hastings England and continued to lecture at the School of Medicine for Women.

In 1907, in Scotland, she fell down a flight of stairs which left her mentally and physically disabled. In 1910, she died at her home in Hastings Sussex after suffering a paralyzing stroke.

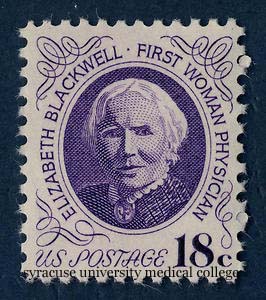

HONORS

- Elizabeth Blackwell is honored as an alumna of both Hobart and William Smith Colleges and the State University of New York Upstate Medical University.

- Since 1949, the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal has been awarded annually to a female physician by the American Medical Women’s Association.

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges awards an annual Elizabeth Blackwell Award to women who have demonstrated outstanding service to humankind.

- In 1973, Elizabeth Blackwell was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

- In 2013, the University of Bristol launched the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research.

- February 3, 2016, National Women Physicians Day, was declared a National Holiday which pays tribute to Dr. Blackwell for the role she played in influencing women physicians in the present day in their striving for equity and equality.

- In May of 2018, a commemorative plaque was unveiled at the former location of the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children.

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges erected a statue on their campus honoring Blackwell.

- A 2021 book by Janice P. Nimura, 'The Doctors Blackwell,' chronicles the life story of Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister, Emily.

- The Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York has named a street in the medical complex, in her name. The Syracuse University College of Medicine took over the Geneva Medical College in 1871, which was then acquired in 1950 by the State University of New York (SUNY) Upstate Medical University.

Top of Elizabeth Blackwell

"The Cleanest Clean You've Ever Seen."

by

ABC Oriental Rug & Carpet Cleaning Co.

130 Cecil Malone Drive Ithaca, NY 14850

607-272-1566